Icons, because of their importance to worship in the Eastern Church, must have certain properties, images and motifs.

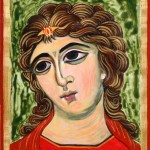

- First and foremost, icons are executed in silence and prayer. They are a sacred meditation for the iconographer, and this serene quality is manifested in the work. Icons are meant to be contemplated for their spiritual import rather than admired for their beauty. Nevertheless, their vivid colors and graceful lines many consider to be powerfully beautiful.

- The images are to be recognizable, but it is their spiritual meaning that is important, not their depiction of nature or a worldly conception of beauty.

The Orthodox iconographer tries to express the supra-natural, transfigured elements of people and events through hyperbole, exaggeration, even deformation of the natural reality. These deformities have a symbolic meaning, and help the viewer “read” the icon. For instance, big eyes indicate that the saint sees God’s perspective on things better than we worldly creatures do.

The Orthodox iconographer tries to express the supra-natural, transfigured elements of people and events through hyperbole, exaggeration, even deformation of the natural reality. These deformities have a symbolic meaning, and help the viewer “read” the icon. For instance, big eyes indicate that the saint sees God’s perspective on things better than we worldly creatures do.  Small mouths indicate that the saint has no longer need for worldly food, as he has received all the nourishment he needs from God. The baby Jesus often is shown as a small mature person because He is believed to have the wisdom and reason of the mature Jesus from His birth. Thus, the viewer, as he notices that an element seems exaggerated or “unreal” is invited to explore why the iconographer would have rendered it so, what symbolism this distortion could connote.

Small mouths indicate that the saint has no longer need for worldly food, as he has received all the nourishment he needs from God. The baby Jesus often is shown as a small mature person because He is believed to have the wisdom and reason of the mature Jesus from His birth. Thus, the viewer, as he notices that an element seems exaggerated or “unreal” is invited to explore why the iconographer would have rendered it so, what symbolism this distortion could connote. - The opinions, inspirations, intuitions and innovations of the iconographer are irrelevant and therefore to be shunned. In the West these qualities are encouraged; the artist is expected to have something new to say if he is to be of any account.

- The idea that there is only one “Truth” is emphasized by making all the saints look alike. Sometimes it is only by his attributes that a saint can be identified, because all physiognomies are much the same except for the hair. For instance, St. Andrew is usually shown with the saltire cross upon which he was crucified, St. John the Evangelist holds the Gospel book open to his most quoted sentence: “In the beginning was the Word…” ( Each saint should be identified by name on the icon, but sometimes the names have been obscured through the ages).

- Reverse perspective, a method of structuring the figures according to (unseen) geometric outlines, arranges the lines of perspective towards the viewer in order to draw him/her into communication with the persons in the icon. The structure and the figures are arranged symmetrically so that the focal point is Christ or the Mother of God.

- Icons ignore time and space. The value of a subject determines its size and position in the layout, with the possibility of portraying simultaneously scenes that historically took place in different times and locations. For example, in the icon of the Nativity, the main scene of the birth is in the center. Around it are smaller scenes of related events of the early life of Jesus. The importance of a figure will determine its size in the icon, so that one can quite literally speak of spiritual giants.

- In early Christian centuries a variety of mediums were used for icons: marble, ivory, tapestry, mosaics, gold, silver, enamel, terra cotta. Most commonly, however, icons were painted on a gessoed wood panel in encaustic, or hot wax. The wax allowed light to penetrate the colors, bounce off the white gesso background, and refract back to the viewer, making the colors more vivid, and giving the icon a glowing quality. Unfortunately, encaustic is very flammable and not very durable, so around the ninth century, egg-tempera was substituted. The glowing quality is not as great as with wax, but it is perceivable.

- In the twentieth century, acrylics were developed which have some of this quality. Oil paint can allow light refraction, too, if it contains sufficient oil. But this paint takes so long to dry that it is impractical to use, due to the painting method required by the Church.

- This method is dark to light, unlike most painting. The first paints applied to the gessoed panel are the darkest of the darks used in the work, symbolizing the chaos of the world before creation. Subsequent layers (each containing its own symbolism) are applied building up the highlights meaning that the light of heaven overcomes the dark and issues from Jesus-as-God, (and his life, and his servants and Mother) not from some source outside of God. Often the fleshy parts of the icon require six or seven layers to build up the light tones; thence the need for a medium which will dry quickly. Even small icons can take over a week to paint – and that doesn’t include the days required to prepare the panels with a dozen or so coats of gesso.

The unique or different is banned in iconography. There are no new icons, only reverently recreated traditional icons. To the Orthodox, if a depiction has been accepted as “true”, it should be used as a guide for a newly rendered icon. God is asked to inspire the artist and guide his hand. Because God is the true artist, icons were not signed by the iconographer until relatively recently.

How Icons are painted: